Adelaide Festival of Ideas: The Joy MacLennan Oration

By Peter Sandeman

This oration honours the work of Joy MacLennan, a former social worker at the Church of England Social Welfare Bureau, the forerunner of AnglicareSA.

Through her service, spanning thirty years, she pioneered the connection between our Church and social services. Through her collation of data on thousands of vulnerable South Australians, she became a voice for voiceless within the Church community. She developed links between our community and the National Council of Women and the Council of Social Services – which later became SACOSS and ACOSS.

Her dedication to the Church and commitment to faith-in-action has left an enduring legacy.

Joy represents a great many good people in our community through whose quiet efforts, the lives of so many others have been so positively impacted in ways that still ripple throughout our community.

We think of ourselves as an egalitarian society and certainly, within the broader population, we do not suffer the same issues of class that plagues the English experience. Nonetheless, while the forms may differ, the mechanism and outcomes of exclusion work against many groups in Australian society.

One of the most obvious is the increasing disparity of income and wealth in Australia, along with other western societies.

An increasing disparity of income & wealth

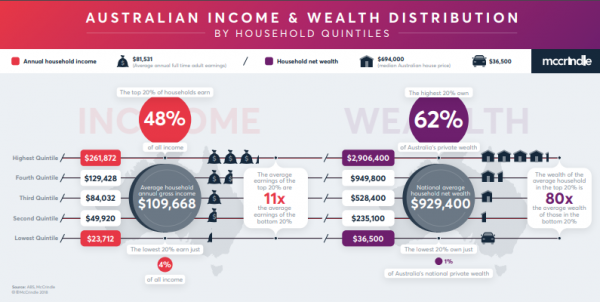

There are various measures of inequality; one is to compare the Income and Household wealth of the lowest to the highest quintile or the five cohorts each of 20% of the population.

In terms of household income, the bottom 20% of households have an average income of $22,620, the second quintile has an average income of $47,944, the third or middle quintile has an average household income of $80,704, the fourth quintile has an average household income of $124,956, while the top 20% have an average household income of $260,104. This is more than double the average household income overall which is $107,276.

And just in case your mental arithmetic isn’t up to scratch on this sleepy Sunday afternoon: this means the top 20% of households, have on average twelve times the income of the bottom 20% of households.

Or to put it more bluntly, the top 20% of households have 49% of all income, while the bottom 20% of households have 4% of all income.

Source: https://mccrindle.com.au/insights/blog/australias-household-income-wealth-distribution/

And it’s worse still when we compare household net worth; The bottom 20% of households are worth on average $35,500, this jumps to the next quintile which has an average net worth of $206,100. The Middle quintile has an average household net worth of $462,500 and the fourth quintile is worth an average of $830,600 while the top 20% are worth on average of $2,514,400.

On average, the top 20% of households have 71 times the net worth of the bottom 20% of households and own 62% of private wealth while the bottom 20% own just .9% of private wealth in Australia. (Kimmorley, 2016)

Using the Gini coefficient with zero being perfect equality and 1 being total inequity, Australia is facing the most unequal level ever seen, at .446 compared to .417 in the 1990’s. (Kimmorley, 2016)

And it’s not just Australia, net inequality has risen in the OECD over the past several decades as redistribution has not kept pace with the rise in market inequality. (Ostry, 2014, p13)

What is clear is that our society is becoming less equal – but does that really matter unless you are one of those trapped in the lowest quintile?

At AnglicareSA, we see the impact of the market inequality on the poorest and most marginalised individuals and communities in South Australia every day, our basic emergency assistance, food and clothing services are overwhelmed.

Our homelessness services and housing services are often stretched beyond capacity and we see the impacts of poverty on family dysfunction. We see devastating effects of domestic violence, as well as the abuse and neglect of children.

While the left has traditionally emphasised the need for redistributive policies to ameliorate the worst effects of the market on the poorest, the right has worried about the impact on the efficiency of the market.

The call to lift the appallingly low rate of Newstart unemployment allowance is the current focus of this conflict. Could anyone here live on the princely sum of $40.00 per day?

Yet such is the state of Australian politics today that the government has refused any increase to the level of Newstart, while the opposition merely promises a review – and conveniently omits to mention that their last government tipped single parents into the abyss of life on Newstart on their youngest child’s eighth birthday.

“Do we dare say we live in dark times?”

As Robyn Archer asked in her dystopian keynote address to open this Festival of Ideas; “Do we dare say we live in dark times?”

The lingering anger from the Depression era directed towards the dreaded army of “dole bludgers” rests the assumption that the unemployed need to be compelled to find work in order to sustain the efficiency of the labour market and keep wages well in check.

Keeping unemployment benefits well below the minimum wage is seen as vital to market efficiency.

Source: https://www.sharethepie.com.au/

Many commentators have expressed a concern that low wage growth is now a major constraint on economic growth. It seems the Newstart lever has been too effective in dampening wages growth and there are sound economic reason to raise Newstart above the abject poverty, which is the fate of the long-term unemployed.

As the Co-chair of Anti-Poverty Week this year I will be lending my support along with many others, including the Business Council of Australia and the Anti-Poverty Alliance of South Australia, to “Raise the Rate”.

AnglicareSA’s vision is “justice, respect and fullness of life for all” inspired by the radical inclusion of the Gospel of Jesus and based on the unlikely premise that all lives are equal. It’s a notion that respect and true justice requires a little extra effort to include those most likely to be excluded.

The question is, of course, in the famous words of Vladimir Lenin – “What is to be done?” – which is the title of the pamphlet where he argues for a broader understanding of social and economic conditions and the strategies required, rather than simply the struggle of unions to raise the wages of workers. (Lenin, 1901) Wage justice is important but it is not a sufficient solution to inequality and economic stagnation.

Nor, for example, is the campaign to raise Newstart, necessary as it is for relief of immediate poverty of the long-term unemployed, a sufficient solution to advance either market efficiency or equity in the longer term.

The need for economic development & equity

What is urgently required is a strategy to advance the social and economic wellbeing of South Australia, our Cinderella state, with a major capacity for self-doubt.

Can we simultaneously advance both market efficiency, in order to create the wealth we require to sustain our population, as well as advance our collective well-being, the social and economic equity, which would enable us to be truly an inclusive and liberal democracy?

I believe that we can have both economic development and equity. In fact, I want to argue that greater equity is an essential requirement of the economic advancement of South Australia.

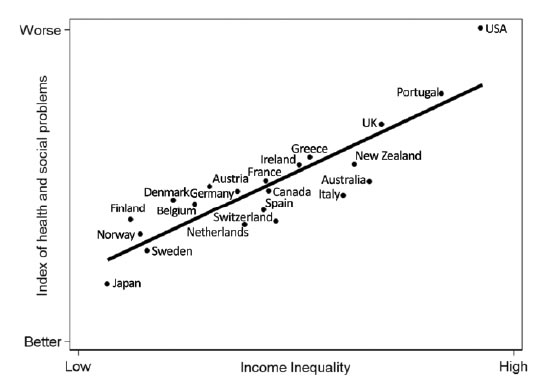

Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett in their ground breaking book The Spirit Level, convincingly demonstrated that for wealthy countries, it is the degree of income inequality rather than average income which is closely related to a range of health and social problems. The greater the inequality, the poorer the health and social outcomes in that country. (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009, p 20)

In other words, it is the relative poverty, the disparity between incomes, which is the problem rather than absolute poverty per se in our post industrial society, as opposed to the conditions in third world countries where absolute poverty to the point of starvation and malnourishment is the grim reality for many.

Perhaps the most interesting part of Wilkinson and Pickett’s thesis is that greater inequality seems the heighten the social anxieties of people through increasing the importance of social status. This means the rise of both fragile self-regard and anxiety. (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009, p43)

This, in turn, means that levels of trust between members of the public are lower in countries where differences in incomes are higher. (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009, p52)

We know trust and reciprocity are the hallmark of social capital, the relationships which bind us together as a community and lower the transaction costs of economic activity and a foundation of market efficiency.

In his ground-breaking book Bowling Alone, Robert Putnam cites the concomitant decline in social capital and growth in inequality by suggesting the causation would lie in both directions. (Putnam, 2000) This is another classic which should sit on your bookshelf at home.

Putnam’s thesis is that social capital in the United States has been declining. He gives the graphic example that while Americans are ten pin bowling as much as before, they no longer bowl in as teams in organised leagues but rather now tend to bowl alone.

Likewise we see the decline in social organisations in Australia such as service clubs, churches and even, to chagrin of many hacks, membership of political parties.

It is the people in the bottom quintile who have most to resent, and perhaps those who see themselves as precariously occupying the second quintile who, fearing their descent into the bottom twenty percent, who are prone to identify “the other” who is the root cause of their disadvantage.

These resentments can cause conflict between groups within the community and fuel populist politicians – the Trumps and Hansons of the world – who take advantage of real or perceived injustices. These disruptions due to inequality can be major hindrances to economic development.

Greater equality will underpin greater economic growth

My argument is not simply about making South Australia a nicer place to live through greater equality, although that would certainly a pleasant by-product, but rather that, in a very real sense, greater equality will underpin greater economic growth.

Inequality has risen so much that it is becoming a brake on economic development, and the traditional approach of western democracies has been to combat these effects through redistribution policies and programs.

Traditionally the economic policy literature has assumed redistribution hurts growth as higher taxes dampen incentives to work and invest.

One critique of the classic focus on the growing disparity in income and wealth is that often analysis is based on market inequality (before taxes and transfer payments), rather than net inequality (after taxes and transfer payments) taking into account redistributive efforts. (Ostry, 2014, p4)

Taking these redistributive effects into account, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) conducted a cross country analysis of the relationship between net inequality and market efficiency.

Empirical data from across countries across the world in this IMF study found a strong negative relation between the level of net inequality and growth in income per capita, and given the episodic nature of growth, a strong negative relation between the level of net equity and the duration of growth spells. (Ostry, 2014, p16)

The tentative consensus in the growth literature is that inequality can undermine progress in health and education, cause political and economic instability reducing investment, and undercut the social consensus required to adjust to major shocks and thus reduce the pace and durability of growth. (Ostry, 2014, p8)

Higher inequality therefore lowers growth, and these findings are repeated in the formal briefing provided to members of Federal Parliament; that more egalitarian societies tend to have lower steady state unemployment and higher rates of technical progress and productivity growth. (Holmes, 2018)

To the extent it lowers inequality, the IMF study found that if anything, redistribution has a slight positive effect. (Ostry, 2014, p17)

Comparing the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores of 15 year olds shows international education attainment is closely related to income inequality, mediated through the impact of inequality on family life and relationships. (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2009, p110)

Inequality reduces performance because of its segregating effects, the influence of peers is greater that of any other school effects including teacher quality. If children from lower socioeconomic disadvantaged backgrounds only mix with children from similar backgrounds then inequality may cause a reduction in educational attainment. (Holmes, 2018)

By measuring the relative performance of 15 years olds around the world, PISA demonstrates the impact of segregated schooling systems in the inequality of outcomes compared to integrated schooling where the mix of students from different backgrounds tends to overcome the differences in student backgrounds. Integration of schooling lifts the tail in performance without reducing the higher achievements.

So it’s not just the quantum of funding that Federal Education Minister Simon Birmingham needs to get right but also tackling the increasing division of children into segregated schooling systems. And it’s important for economic growth because if children are less successful at school they are less likely to become skilled workers, OECD research concludes that policies to improve high school and tertiary education completion rated also improve gross domestic product per capita. (Holmes, 2018)

Income inequality causes poor health

The same type of impact on inequality and hence economic development applies to health.

Research shows that in high income countries, income inequality causes poor health, possibly through stress, the World Health Organisation research shows that in Europe more unequal countries have poorer mental health outcomes. (Holmes, 2018)

Source: Wilkinson R, Pickett K. The spirit level. London: Allen Lane; 2009.

Adelaide’s very Own Professor Fran Baum and her Southgate Institute for Health, Society and Equity at Flinders University provide world-leading research into the social and economic determinants of health. Economic inequality has been conclusively demonstrated to be a major determinant of ill health, and therefore a major effect in retarding economic growth.

Better targeting of health and education systems towards the poor would have both a substantial effect on reducing inequality and enhancing growth, enabling many more people to lead more productive lives in a virtuous spiral of mutually reinforcing economic growth and wellbeing.

To return to the question posed by Lenin, “What is to be done?” in South Australia, what new thinking, what can we do to combat inequality and promote growth if redistribution is governed elsewhere?

I believe thinkers such as Muhammad Yunus in his example and his writings have shown us the way, Earlier this year, our MC today David Pearson gave me a copy of Muhammad Yunus’ 2017 book “A World of three Zeroes”. The subtitle of the book is “The new economics of zero poverty, zero unemployment, and zero carbon emissions”, and yes it’s’ another book I strongly suggest we should all have on our bookshelves. (Yunus, 2017)

Yunus argues cogently that traditional economic thinking says that selflessness cannot be part of the business world, which can only be about the selfish maximisation of profit and relegates generosity to only be expressed through philanthropy. Yunus asks why shouldn’t the business world be an unbiased playground offering scope for both selfishness and selflessness? (Yunus, 2017 p 27)

To alleviate poverty in the third world Yunus developed through the Grameen Bank offering micro credit loans to the poor which have lifted many people and their communities out of poverty. In collaboration with major business organisations and their leaders, Yunus has also developed the concept and the practice of Social Business.

Social Business offers great advantages which are not available to either to profit maximising companies nor to traditional charities which is of course where AnglicareSA has come from.

Freedom from the for profit pressure and the demands of profit seeking investors helps make social businesses viable, even in circumstances which make current capitalist markets fail. And because social business is designed to generate revenues and thereby become self sustaining, it is free from the constant need to attract new streams of donor and government funding to stay afloat. (Yunus, 2017, p40)

And today through directions set by the Productivity Commission’s report into Human Services (Productivity Commission, 2016), and the combined weight of Consumer Directed Care in community aged care and the National Disability Insurance Scheme, community sector agency like AnglicareSA are transforming themselves into social businesses (albeit with varying degrees of enthusiasm and success), as the funding is now in the hands of their customers.

The need for Social Business & Social Enterprise in South Australia

Yunus established Social Business Action Tanks, which is a gathering of top executives from large corporations to launch and build social businesses alongside their mega conventional businesses to address social problems. (Yunus, 2017, p60)

For example through the French Action Tank, Renault looked at the cost to the 13% of the French population identified as being unable to maintain their old cars as a major barrier to employment and wellbeing. Initially the thought was to develop a low cost car but modelling identified this would still be too expensive and the poorer members of the community would retain their older cars which were unreliable and expensive to maintain.

Instead Renault launched the Mobiliz Social business to provide low cost car servicing to low income car owners through “solidarity garages” to keep their cars on the road while also serving non discount clients to fully cover their costs. (Yunus, 2107, p63)

In Australia a local version of an Action Tank is Social Traders and they use the language of Social Enterprise which seems to permit a degree of for profit while Yunus requires proceeds to be ploughed back into the social business. These categories seem to not the be strictly adhered to with some blended models of social business and social enterprise.

Social Traders defines Social Enterprises as

- Led by an economic, social, cultural or environmental mission consistent with a public or community benefit.

- Trade to fulfil their mission

- Derive a substantial proportion of their income from trade

- Reinvest the majority of the profit /surplus in fulfilment of their mission.(Social Traders, 2016)

Social Traders sponsored a survey Finding Australia’s Social Enterprises in 2016 which identified 20,000 social enterprises in Australia:

- 73% are Small businesses, 23% medium sized and 4% are large.

- 54 Social enterprises identified in SA.

- Philanthropic support 12% of income, up from 7% in 2010 (Social Traders, 2016),

In its 2018 survey of South Australian Social Enterprise in conjunction with the Don Dunstan Foundation, the SA Centre for Economic Studies identified 77 Social Enterprises operating in South Australia. (Cebulla, 2018)

While this is still a relatively small pool, we have some great examples of social business and social enterprise in Australia.

KiK, South Australia was initiated by Louise Nobes in 2016.

Source: InDaily

Louise had been a social worker for 15 years working with young people in community services, child protection and welfare services in South Australia.

Despondent by the ongoing level of disengagement and barriers faced by young people in the workforce, Louise looked for new solutions to tackle the complex problems of youth unemployment

Louise was inspired do this by engaging young people through “entrepreneurial doing “, and empowering them to create their own solutions.

This led to the KiK brand, which is now a group of companies that employs over 25 young people.

KiK has trained 82 young people and supported 62 in terms of supported pathways.

We need to learn more about KiK and learn from Louise.

Social Business and Social Enterprise have much to offer in a state where we are devoid of corporate head offices, the redistributive levers are elsewhere, and we have burgeoning youth and adult unemployment and disadvantage growing social and economic inequity.

We need to establish our own South Australian Social Business Action Tank, to bring enterprise and social action together, to help foster and grow social business. Without the need to provide profits to investors, social business will create the jobs and economic activity to reduce inequality and its blight on lives of so many people, and the drag it creates on economic growth.

It’s a movement we need to join, to encourage and to invest in.

As individuals we can make a difference.

Just like Joy McLennon we can effect the lives of others and make a real difference

Social Business will make South Australia great again.